by Janina Fisher

In a threatening world, with no support, protection, or comfort, children have to rely upon the limited resources of their own bodies to manage overwhelming circumstances and unbearable feelings. Infants have the fewest resources because the body and nervous system are still immature at birth, yet even a baby can dissociate or go into a limp, numb parasympathetic state. Toddlers and preschoolers have a few more options. They can use food to soothe themselves and masturbate to stimulate pleasurable feelings. They can also stimulate adrenaline production through hyperactive or risky behavior. As children reach latency and early puberty, even more options become available: They can restrict food, binge and purge, develop obsessive-compulsive patterns of behavior, act out sexually, pinch or scratch themselves, and even fantasize about suicide. Less self-destructive coping can also develop: getting lost in books or fantasy, parentified behavior, or over-achievement.

In adolescence, the growing physical strength and capability of the body facilitates a new array of options for self-regulation. Running away is now a choice. Teenagers also have greater access to cigarettes and drugs, or they can act out sexually, engage in more severe eating-disordered behavior, and have the strength to act on suicidal impulses. The physical body is now capable of violence, whether aggressive behavior toward others or self-inflicted violence, unchecked by an inhibited or immature prefrontal cortex. As the saying goes, “Desperate times call for desperate measures,” and often desperate self-destructive measures are a well-conditioned pattern of response by the time traumatized children reach adulthood.

Ask yourself, “How old was I when I first started to _____________________ as a way to manage my feelings?”

Desperate Efforts to Regulate a Traumatized Nervous System

Every type of addictive, eating-disordered, and self-destructive behavior produces a neurochemical reaction in the human body. Let us take a closer look at some of the common ways in which trauma survivors attempt to regulate their trauma responses.

Self-injury (cutting, head banging, punching walls, or even hitting ourselves) brings quick relief to the body by stimulating the production of adrenaline and endorphins, two neurochemicals that decrease pain. As discussed in the previous chapter, adrenaline produces a surge of energy and a physical sense of strength, and it also induces a state best described as “calm, cool, and collected.” Doctors, nurses, and EMTs all rely on adrenaline to do their jobs well, as do most peak performers. Endorphins are the neurochemicals associated with relaxation, pleasure, and pain relief; they are the body’s “happy” chemicals. The combination of these two chemical responses triggered by self-harm is responsible for the very immediate and complete physical and emotional relief felt by those who self-injure.

Restricting food intake puts the body into a neurochemical state called ketosis, creating a numbing effect but also a boost of increased energy. No wonder individuals with anorexia can eat so little and still work out at the gym for hours. Binging and overeating, on the other hand, both have a numbing and relaxing effect.

Drugs (whether illicit substances or prescription drugs) cause many different effects, from sedation and numbing to stimulation and increased feelings of power and control. Alcohol is a mild stimulant in small doses and a relaxant in larger doses, bringing some relief to trauma survivors who experience both anxiety and depression. Marijuana serves the purpose of inducing a steady state of hypoarousal and numbing, especially when taken at intervals throughout the day.

Compulsive hyperactivity, workaholism, and high-risk behavior of all kinds also tend to stimulate adrenaline production, whereas retreating to one’s bed and curtailing activity tends to increase feelings of spaciness and numbing.

Long before substance use becomes abuse or self-harm becomes active suicidality, trauma survivors initially learn that they can successfully control their symptoms and function in the world by using their drugs and behaviors of choice. I use the term successfully because, to the extent that substance use, eating disorders, or self-harm bring symptom relief to the survivor, it may prevent suicidality, loss of functioning, social withdrawal, and a host of other problems common to those who have been traumatized.

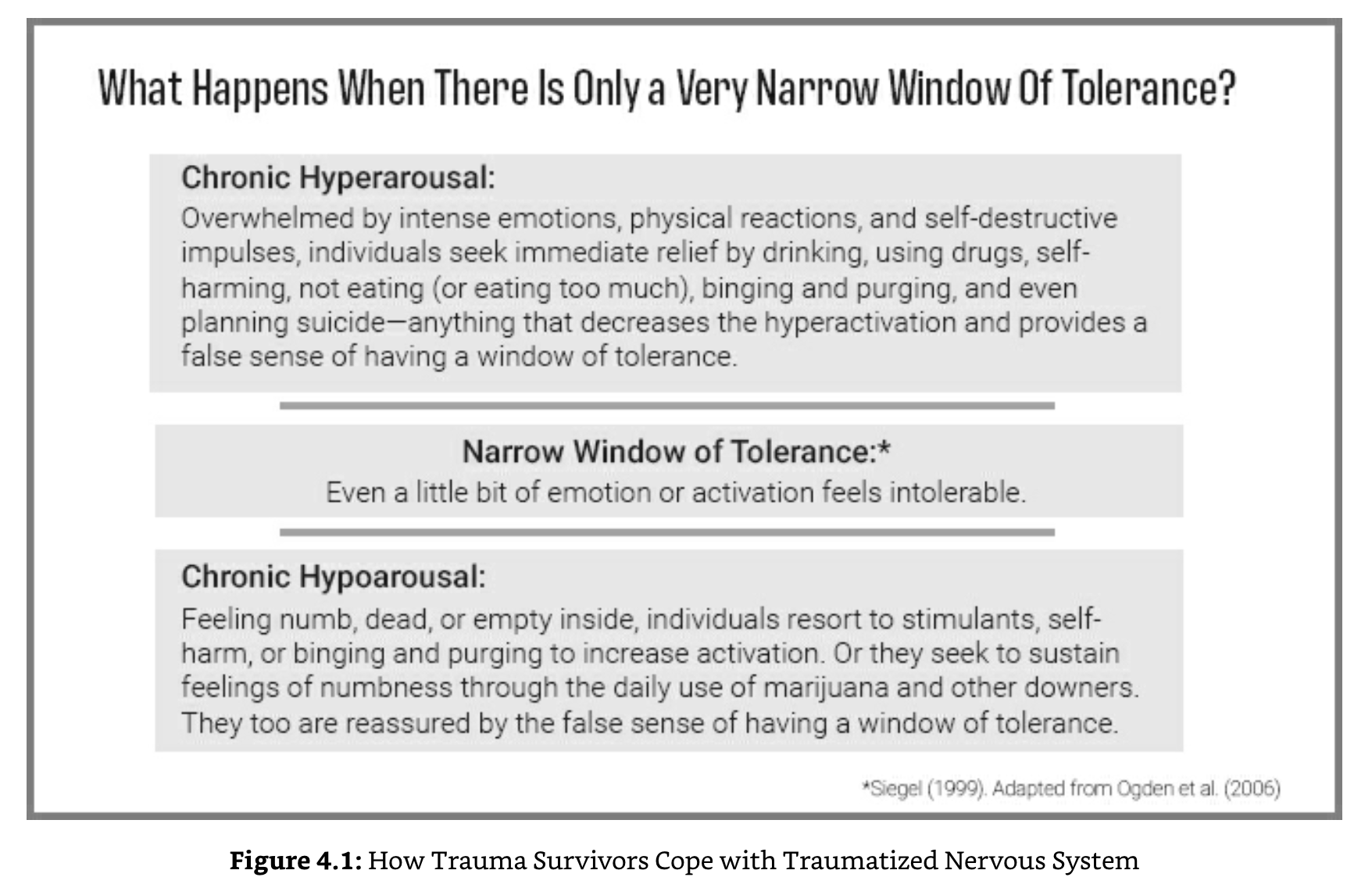

Figure 4.1 illustrates the ways in which people instinctively try to cope with their hyper-or hypoarousal in order to get relief. These behaviors provide a temporary false window of tolerance, offering a sense of “I can handle this” that is time-limited and illusory.

Turn to Worksheet 10: How Do You Try to Regulate Your Traumatized Nervous System? to explore how you have learned to regulate yourself. How do you try to manage your nervous system and distressing emotions? What is your “go-to” way of feeling better? Your second most familiar way of trying to manage traumatic activation? Do not judge yourself—just be curious about how these behaviors help! Whatever you notice will not only help you understand your actions and reactions as ways you are trying to help yourself, but it will also tell you more about how you survived. Was survival dependent upon staying frightened and on guard? Ashamed and people-pleasing? Or shut down and numb? Or being constantly on the run?

The Vicious Circle of Addictive and Self-Destructive Behavior

Any addictive or self-destructive behavior begins as a survival strategy: as a way to numb, wall off intrusive memories, self-soothe, increase hypervigilance, combat depression, or facilitate dissociating. But compulsive behaviors also have a “drug effect” that wears off after a few minutes or hours, increasing the sense of need or urgency to repeat the action or substance to prevent losing that positive effect. With repeated use, the body develops tolerance, meaning that these psychoactive substances (whether alcohol, heroin, or the body’s own chemicals like adrenaline) require continual increases in dosage to maintain the original degree of relief and eventually are needed just to ward off physical and emotional withdrawal effects.

Were it not for the body’s increasing tolerance, trauma survivors could use these means of obtaining relief in a moderate, low-risk way for years. Instead, over time, eating disorders become increasingly worse, substance use becomes abuse, self-harm becomes more dangerous, and suicidal thoughts and wishes become more actively life-threatening. Thus, the substance use or self-destructive behavior may begin as an effective approach to managing post-traumatic reactions, but then it gradually acquires a life of its own, becoming increasingly disruptive to the survivor’s functioning until it is a greater threat than the symptoms it attempts to keep at bay.

Once the thinking brain matures in our 20s, we have more capacity to appreciate the consequences of unsafe behavior and more ability to think before we act, but that increased awareness often results in shame: “Why am I doing this? If anyone knew, they would judge me. I need to stop, but I can’t!” Survivors may hate themselves for using these ways of coping, but the alternative is worse. The emotions and implicit memories that were dangerous to feel or acknowledge long ago still trigger the same sense of threat—and the same desperate need to stop them at all cost.

Without understanding the method to their madness, the logical conclusion most trauma survivors reach is: “There must be something wrong with me—I must be defective.” Their shame and self-blame of course trigger more intense, intolerable feelings—further increasing the need to do something to make the feelings stop. They are now literally, as the saying goes, “between a rock and a hard place.” If they stop the behaviors that stem the tide of overwhelming feelings, then the feelings will be even more intolerable. If they do not stop, the shame worsens into self-hatred. Few trauma survivors realize that their self-destructive behavior represents an ingenious attempt to regulate their nervous systems and their unbearable physical and emotional reactions.

When you are a trauma survivor who has learned to manage overwhelming feelings using addictive, eating-disordered, or unsafe behavior, it takes more than this book alone to address both the trauma and the ways you are coping with it. This way of thinking about how you have learned to survive and adapt, however, is an important first step. In the next chapter, we address how to observe and begin to change high-risk patterns for managing traumatic responses.

Fisher, Janina. Transforming The Living Legacy of Trauma: A Workbook for Survivors and Therapists. PESI Publishing & Media.